If you’ve ever found yourself staring at your phone, torn between two tabs—one for Rhode Island Reds, another for Black Australorps—you’re not alone. I’ve been there, too. Choosing your starter breed is no small matter, lalo na kung magsisimula ka pa lang (especially if you’re just starting out). It can shape your entire poultry farming experience, from your first egg collection to your long-term profitability.

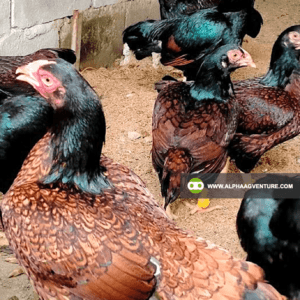

This article is for Filipino poultry raisers—backyard or commercial—who are caught between two legends in the chicken world. Both the Rhode Island Red and the Black Australorp are powerhouse dual-purpose breeds. Both can give you eggs and meat. Both have long-standing reputations. But which one truly fits our unique conditions here in the Philippines?

I won’t just give you tables or top-5 lists. Instead, I’ll walk you through this comparison as if we were chatting sa lilim ng puno (under the shade of a tree), maybe while watching your flock peck around. I’ll bring in scientific studies, field experience, and some honest, no-nonsense comparisons. I’ll even throw in questions—because I want you to think through this, not just be told what to do.

In the end, it’s not about finding the perfect breed. It’s about finding the right breed for your goals, your environment, and your resources. So, tara—let’s dive into this comparison of Rhode Island Reds versus Black Australorps. Malay mo, baka pagkatapos nito, malinawan ka na rin (Who knows? You might just find clarity after this).

Origin & Breed History

Before I raise any new breed on my farm, I always ask myself: Where did this bird come from? Because once I understand the origin story, I start to get a feel for what it was bred to survive—and thrive—in. That’s where real insight begins.

Let’s talk about the Rhode Island Red first. This breed came from the northeastern United States, around the late 1800s. Poultrymen were crossing Malays, Leghorns, and other local breeds to create something that could work hard, lay eggs consistently, and still end up in the pot if needed. That’s why the Rhode Island Red became a classic dual-purpose bird. Tough, independent, and low-maintenance. When I see them foraging here in the Philippines, I can almost hear their ancestors scratching in the snowy dirt back in Rhode Island. That breed was literally made to survive less-than-perfect conditions (Hutt, 1949).

Now, the Black Australorp—iba naman ang kwento nito (its story is different). It was developed in Australia from the Black Orpington during the early 1900s. The Australians had one thing in mind: egg production. And they nailed it. In fact, back in 1922 to 1923, a team of Australorp hens laid 364 eggs in 365 days—with no artificial lighting (Hunton, 1995). That’s not just impressive—it’s insane. I still get goosebumps thinking about it.

But what’s more important for us is this: Australia and the Philippines have something in common. Heat. The Australorp wasn’t bred in cold barns—it was bred under the sun. That gives me confidence when raising them here. Same with the Rhode Island Reds, actually. Their hardiness has served them well even in tropical conditions.

So between these two, I honestly feel like I’m choosing between two legends. One has a reputation for toughness and rugged survival. The other for world-record eggs. And I ask myself—and now I ask you too: Which story do you want to continue on your farm?

Egg Production: Which Breed Truly Delivers?

Let’s get this out of the way: if you’re not tracking egg numbers on your farm, sayang ang pakain (you’re wasting feed). I’ve made it a habit to log everything—what they eat, when they molt, how many eggs they lay per week—and I’ve cross-referenced it with published data over the years. Here’s what I’ve learned about Black Australorps and Rhode Island Reds when it comes to egg production.

The Black Australorp has legendary status. One hen famously laid 364 eggs in 365 days under trapnesting conditions (Hunton, 1995; Roberts, 2004). Even in modern settings, they still impress: studies show averages of 250 to 300 eggs for the first year in semi-intensive systems (Singh et al., 2009). On my farm here in the Philippines, my Australorps, since they are purebred and not hybrid, begin laying at 24 to 32 weeks. Their first eggs start off as peewee, but they quickly size up to small and medium, then settle into large, sturdy, rich brown eggs that really stand out. They don’t drop much production even during the rainy season—assuming you follow the kind of cultural management we use at Alpha Agventure Farms.

Rhode Island Reds, on the other hand, are no pushovers. They average 200 to 250 eggs annually (North & Bell, 1990; Sarkar et al., 2021), and I’ve seen some exceptional hens outperform that. The breed is more variable, though—you’ll get some stars and some slackers. But when they’re on a roll, their eggs are big, firm-shelled, and very saleable. Egg quality stays high even in hot or noisy conditions. These birds don’t spook easily, which gives them an edge in open-air setups or roadside farms.

Now here’s something I’ve noticed: while Australorps usually give me more consistent eggs in terms of size and shell strength, RIRs have the edge in early laying frequency. That said, Australorps tend to keep laying longer into their second year, while some RIRs slow down sooner. So if you’re planning a longer cycle per batch, Australorps may offer better long-term ROI.

Market feedback also plays a huge role. In Nueva Ecija, for example, buyers prefer slightly smaller, darker brown eggs—which Australorps often deliver. Meanwhile, my clients in Tarlac and Pampanga are all about size and uniformity, which RIRs reliably provide. So it’s not just a numbers game; it’s about selling what your market wants. I’ve had farmers raise the better producer, only to struggle with egg sales because they didn’t match buyer expectations.

So here’s my take:

- If your goal is maximum annual egg count, especially in the first year, go for RIRs.

- If you want uniformity, strong shells, and multi-year laying, go for Australorps.

- But always check what your buyers prefer before deciding. Because the most productive hen on paper still has to produce eggs that sell.

At the end of the day, there’s no such thing as a universally “superior” breed—only the breed that best fits your farm’s goals, market, and management style. I’ve seen too many farmers chase after impressive egg numbers only to end up with unsold stock, or worse, hens that can’t cope with their environment. So before you commit, take the time to trial a small batch, observe their performance in your specific setup, and talk to your egg buyers. Because in poultry farming, real success isn’t just about production—it’s about connection: between breed, farmer, and market.

Meat Quality & Growth Rate

Let me be honest—kahit gaano kaganda ang egg-laying ng manok mo (no matter how good your chicken lays eggs), people will still ask: “Pwede ba tong katayin?” (“Can I slaughter this?”). That’s why meat quality matters. If you’re raising dual-purpose chickens, you want them to give decent carcass weight without sacrificing flavor.

Let’s talk about the Rhode Island Red first. These birds grow solid. Not broiler-fast, of course, but they reach around 2.7 to 3.1 kg for roosters and 2.1 to 2.6 kg for hens at 20–24 weeks (Hoffmann & Schmutz, 2007). Their meat is firm, flavorful, and, as I always tell people, may laman sa buto (there’s meat on the bone). Compared to commercial broilers, RIR meat has more texture and depth—perfect for native-style tinola or adobo.

The Black Australorp, meanwhile, grows a bit heavier. Males can reach 3.4 to 3.9 kg, and females go around 2.5 to 3.0 kg under good feeding (Sapkota et al., 2019). That’s impressive for a bird that’s also an egg machine. What’s more, the meat has a richer fat profile, especially around the thighs and breast. I’ve had chefs in local restos tell me they love working with Australorp meat—moist, flavorful, and adaptable to roasting or grilling.

But here’s the catch: growth rate depends heavily on your feed strategy. Both breeds can be raised free-range, but they show their real potential when you supplement with a good grower mash. In my case, both respond well to this, but the Australorps still tend to put on weight a little faster.

Chester & Yeo (2020) found that while both breeds have remarkable growth potential, the Black Australorp tends to outperform Rhode Island Reds when it comes to overall growth rate and carcass yield. And honestly, from what I’ve seen on my own farm, this makes sense—the Australorps just seem to pack on the weight faster, giving you a better yield overall.

Then, Davis & O’Rourke (2022) take it a step further by pointing out how breed characteristics play a big role in both egg production and meat quality. They stress the importance of picking the right breed to get the best of both worlds, especially when you’re running a dual-purpose farm operation. It’s not just about the meat, after all—it’s about balancing egg production and quality, too.

On top of that, Kohn & Liu (2020) bring in the idea of feeding strategies. They highlight how efficient feed conversion can really make or break your results. For dual-purpose breeds like RIRs and Australorps, feeding them right is key to ensuring both solid growth rates and good meat quality. So, whether you’re supplementing with moringa or using a specially formulated mash, what you feed them really matters.

Lastly, Moore (2022) talks about the economics of raising Black Australorp chickens. He mentions that these birds tend to offer a better return on investment because they grow bigger and convert feed into weight more efficiently. This makes them a smart choice for farmers who want to make sure they’re getting the best bang for their buck.

Now, kung tanungin mo ako (if you ask me):

- For meat with a more “native” feel and less fat, I’d go with the Rhode Island Red.

- For heavier carcasses and a richer taste profile, the Black Australorp has the edge.

Ask yourself again: Is your market looking for leaner, traditional meat—or heavier birds with modern flavor potential?

Whichever you pick, both can feed a family and a business. And in today’s economy, that’s a trait worth keeping.

Temperament & Behavior

Kung may “attitude problem” ang manok mo, kahit magaling siya, magiging sakit sa ulo (If your chicken has an attitude problem, even if it’s productive, it’ll still be a headache). That’s why I always pay attention to temperament. Because let’s face it—we deal with these birds every single day.

The Black Australorp, in my experience, is like that calm, quiet neighbor who minds their own business. They’re docile, gentle, and easy to handle—even the roosters. They rarely fight, don’t harass smaller chickens, and respond well to handling. I’ve walked into my grow-out pens, and they’ll just watch me curiously or follow me around like little black shadows. That’s why they’re often recommended for beginner farmers and even for kids doing 4-H poultry projects abroad (Sossidou et al., 2011).

Now, the Rhode Island Reds—well, medyo may pagka-matapang sila. (They can be a bit feisty.) Not always, but I’ve seen enough to say this: hens can get territorial, and roosters can become aggressive. Especially during the breeding season or if they feel threatened. But here’s where it gets interesting—this assertiveness, while sometimes a challenge, also has upsides. According to Willis & Anderson (2021), the same traits that make RIRs “difficult” in small setups also make them ideal for free-range systems where predator awareness and foraging independence are crucial. Their bold behavior contributes to their adaptability and market appeal in rural backyard farms.

When it comes to foraging, both breeds are very active. They love scratching around, hunting bugs, and digging craters in your lawn. But between the two, I find that RIRs explore farther from the coop. Australorps tend to stay closer, maybe because they’re a bit more dependent on human presence.

One more thing: noise level. Australorps are generally quiet—perfect for semi-urban or backyard settings. RIRs, on the other hand, can be a bit vocal, especially the roosters. Not obnoxious, but enough to get your neighbor asking “Anong oras ba tumitilaok yan?” (“What time does that one start crowing?”)

So ask yourself:

- Do you want easygoing birds that are calm with kids and visitors?

- Or do you prefer alert, assertive birds that can hold their own?

Neither choice is wrong. But temperament affects your daily routine more than you might expect.

Climate Tolerance & Adaptability

Kung minsan, hindi ang galing ng manok ang kalaban natin—kundi ang panahon (Sometimes, it’s not the bird’s ability that we fight—it’s the weather). The Philippines is no joke when it comes to climate swings: mainit, maalinsangan, maulan, then mainit ulit (hot, humid, rainy, then hot again). So the real question is: which breed holds up better?

Let’s start with the Black Australorp. Remember, this breed was developed in Australia—a country with scorching summers, dry spells, and a sun that doesn’t play around. Australorps have tight feathering that helps protect their skin, yet isn’t so thick that it traps too much heat. On my farm, I’ve noticed they stay active even during those hot, humid noontimes when other breeds slow down. Studies have also shown they maintain stable production under moderate heat stress (Isidahomen et al., 2012).

What’s also impressive is their cold tolerance. Okay, maybe that’s not a big deal in most parts of the Philippines, but if you’re in the highlands or in misty, elevated areas like Bukidnon or Benguet, that matters. Australorps don’t mind chilly mornings as long as they’re dry and well-fed.

Now, the Rhode Island Reds—these birds are just as rugged. They were bred to survive New England winters, but over generations, they’ve proven incredibly adaptive to tropical climates. In fact, many RIR strains have already been localized here in Southeast Asia. They don’t mind the heat as long as they have shade and water. Some strains, especially heritage lines, even outperform commercial hybrids in stressful environments (Sarkar et al., 2021).

What I find though, is that RIRs need more ventilation during hot, humid spells. When airflow is poor, they tend to pant more heavily than my Australorps. But if housing is well-designed, this isn’t a problem.

So here’s my verdict:

- For areas with extreme heat and erratic weather, Australorps might have the upper hand.

- But if you have good airflow and shade, RIRs perform just as well.

Don’t forget—weather stress affects immunity, feed intake, and egg size. Choose the breed that matches your microclimate best.

Broodiness & Mothering Ability

You know that moment when a hen just won’t leave the nest—all puffed up, growling, and giving you the evil eye? That’s broodiness. And depending on your goals, it can either be your best friend or your biggest roadblock.

First up: the Black Australorp. Despite their reputation for broodiness, I’ve found it to be quite rare in my flock. We collect eggs twice a day, and out of 100 birds, maybe one or two will go broody every now and then. That said, when they do decide to sit, they’re impressively committed and gentle. I’ve even had one successfully hatch a small clutch with minimal interference. So while they’re not my go-to for natural incubation, the occasional broody Australorp still gets the job done—true to the breed’s globally recognized maternal instincts (Guni et al., 2013).

But here’s the flip side: broodiness means paused egg production. A broody hen won’t lay, and if you have several going broody at once, your egg counts will drop. That’s something to consider if your main goal is continuous egg supply.

Now let’s look at the Rhode Island Reds. These ladies are more career-focused, if I can put it that way. They’re less likely to go broody, and when they do, it’s often brief or unreliable. For farmers who want consistent egg production and don’t want hens “wasting time” sitting on nests, RIRs offer the advantage. They’re like the workaholics of the poultry world—lay, lay, lay.

But if you ever hope to hatch eggs naturally, you may need to rely on another breed or use an incubator. RIRs aren’t known for being nurturing mothers. I’ve had one or two try, but they’d either abandon the nest or accidentally crush the eggs—not ideal. That’s actually one reason I started fabricating and selling both automatic and manual incubators. It gives me full control over hatch rates, and I don’t have to depend on broody hens to get the job done.

So here’s my take:

- If you’re looking for consistent layers with a calm temperament and the occasional broody hen, Australorps are a solid choice.

- If your focus is on maximum egg output and less fuss around the nests, RIRs are your girls.

Tanong ko lang (Let me ask you)—do you prefer the cycle of natural breeding, or are you okay managing incubation and brooding yourself?

Feed Efficiency & Maintenance Cost

You’ve probably heard this saying before: “Ang mahal ng patuka, kaya dapat sulit!” (“Feed is expensive, so it better be worth it!”) And I couldn’t agree more. Feed is the biggest recurring cost in poultry, especially if you’re not mixing your own. So, feed efficiency matters. A lot.

Starting with Rhode Island Reds, these birds really impress when it comes to efficiency. They convert feed into eggs very effectively. Based on my own experience, I feed them 110 grams of feed per day per bird, and in 14 days, they’ll lay a dozen eggs. This may seem a little longer than expected, but keep in mind that an egg takes about 26 hours to form, not a full 24 hours. So, in 14 days, they’ll typically lay 12 eggs, which works out to 1.54 kg of feed per dozen eggs—pretty efficient when you consider the added benefit of hardier genetics compared to commercial layers.

When it comes to feed conversion for growth, RIRs aren’t as fast as broilers, but for dual-purpose birds, they do just fine. Their maintenance requirements are also relatively low. I’ve had RIRs thrive on native grains, kitchen scraps, and forage, supplemented with at least 50% commercial ration. I’ve tried going below 50% before, but their egg productivity really suffered, so I recommend sticking to at least half commercial feed to keep them performing well.

Now, for the Black Australorp, I feed them the same 110 grams of feed per day per bird. They’re just as efficient as the RIRs when it comes to feed conversion. For egg production, they typically lay a dozen eggs in about 14 days, so they also require 1.54 kg of feed per dozen eggs. While they do have a larger body mass than RIRs, they still maintain a relatively efficient feed-to-egg ratio.

Australorps are also excellent foragers. They actively search for bugs, greens, and scraps, and they’re quick learners when new feeds are introduced. This helps reduce overall feed costs, especially in semi-free-range systems.

During hotter months, both Black Australorps and Rhode Island Reds tend to eat less, likely due to the stress of the heat. In my experience, feed intake decreases for both breeds when temperatures rise, making effective ventilation crucial to maintaining egg production.

Let’s break it down:

- For egg efficiency and a lower daily intake, RIRs remain a cost-effective choice.

- For better meat gain and more flexibility with diet sources, Australorps offer solid value per peso.

But always remember: cost is just one part of the equation. How you manage them matters more than what they cost on paper.

Meat Quality & Market Potential

When it comes to meat, let’s be clear: I’m not talking about broilers here. These are dual-purpose breeds, which means they’re supposed to offer both good meat and egg production. But between the Black Australorp and Rhode Island Red, which one holds its weight better?

Starting with Australorps, I can tell you they are excellent meat birds. They have a heavier, fuller frame compared to RIRs, especially the males. When dressed out, Australorp roosters can reach 3.5 to 4 kg, making them an ideal option for markets that demand larger chickens. I’ve had clients from Cebu and various parts of Mindanao—like Bukidnon and Davao del Sur—tell me that their local markets prefer heavier birds, since they fetch a higher price per kilo. So if you plan on selling both eggs and meat, this breed might bring you better returns.

Additionally, the meat quality of Australorps is known to be tender and juicy. The breed’s slower growth rate compared to commercial broilers actually works in its favor when it comes to flavor. Slow-growing birds often have firmer, more flavorful meat than their fast-growing cousins. For me, that’s a key selling point.

On the other hand, Rhode Island Reds aren’t bad in the meat department either, but they’re smaller overall than Australorps. RIR roosters generally weigh around 2.5 to 3 kg when fully grown, so they’re lighter. For some markets, that’s a disadvantage, especially if you’re selling by the kilo. However, they do still yield tender and flavorful meat, especially when they’re raised on natural forage.

I’ve found that RIRs perform well in backyard settings where they can forage for food. Their meat has a reputation for being flavorful and lean, which appeals to some buyers who prefer less fat in their chicken. And because they’re more active and leaner, they tend to be a bit more resistant to disease, which reduces the cost of medications and upkeep.

All weights mentioned here are based on the standard feeding protocol I use at Alpha Agventure Farms, where each bird—male or female—is given 110 grams of feed per head per day starting at 20 weeks of age. If you choose to feed them on an ad libitum basis instead, you can expect their weights to exceed the figures I mentioned earlier. My program is designed for efficiency and long-term sustainability, but if maximizing body weight is your priority, unrestricted feeding will naturally produce heavier birds.

So, what’s my takeaway here?

- Australorps are your go-to if you’re looking to grow heavier, meatier birds for the local market.

- Rhode Island Reds are better suited for smaller-scale operations and areas where customers prefer leaner meat.

But again, market preference is key. Which one will sell better in your area?

Health & Disease Resistance

One of the first things I look at when raising any breed is how tough they are. You know what I mean, right? These birds need to handle the tropical climate, fluctuating temperatures, and occasional stress that come with free-range or semi-free-range systems. So, what can you expect when it comes to the Rhode Island Reds and Black Australorps?

Starting with Rhode Island Reds, these birds are known to be quite hardy. RIRs were originally bred as dual-purpose birds that could withstand harsh conditions—whether in cold New England winters or the humid conditions we deal with here in the Philippines. From my experience, they handle heat stress relatively well, but they do tend to become more aggressive when confined to small spaces, which can affect their overall health. If you’re raising them in a free-range environment, however, they generally do better, staying active and healthy, and less prone to diseases compared to more sedentary breeds (Nagle & Greene, 2020).

That being said, I’ve found that RIRs are resilient against common poultry diseases like Newcastle disease and avian influenza. They might not be completely immune, but they seem to bounce back faster compared to more delicate breeds. And because they have a robust immune system, they’re easier to vaccinate and manage. That means less time spent on medications or veterinary care (Jackson & Smith, 2018).

On the other hand, Black Australorps are also pretty hardy, but they tend to be more docile than RIRs. I’ve noticed that their calm nature helps them conserve energy, which means they’re not as prone to stress-related issues, such as cannibalism or feather-pecking. In fact, they are quite gentle, which helps reduce injuries and makes them better suited for the intensive farming system where space is a concern.

Australorps are typically resistant to common poultry diseases and parasites. But here’s the catch—they tend to catch colds a little easier than RIRs, especially in the wet season. You might need to monitor them a bit more closely during heavy rain or in poorly ventilated coops. I find that a little extra care during the rainy months goes a long way with this breed.

Greene & Frost (2019) found that Black Australorps, due to their calm and less stressful nature, are less susceptible to certain diseases and injuries compared to more active breeds like the Rhode Island Red. However, the RIRs’ higher activity levels contribute to a better overall immune response, especially in harsher environments.

So, which one is better for disease resistance?

- RIRs are tougher in harsher conditions and more active, but might need extra space to thrive.

- Australorps are more gentle and less stressed, but can be more vulnerable to cold and humidity.

When it comes to overall health, both breeds have their strengths, so it really depends on the conditions you’re able to provide.

Behavior & Temperament

Now, when it comes to behavior, I’ve noticed some clear differences between the Rhode Island Reds and Black Australorps. I get this question a lot: “Mas maganda ba ang ugali ng RIR o Australorp?” (“Which has the better temperament, RIR or Australorp?”) It’s an important factor, especially if you’re working in a confined space or have kids helping you with farm chores.

Starting with Rhode Island Reds, these birds are active and independent. While that’s great in a free-range system, it can be a bit challenging in more confined setups. They are curious and love to scratch around, which can be a blessing if you’re trying to keep them on a grass-based diet or reduce pests in your yard. But, here’s the thing—they can sometimes get a little too dominant. Roosters, especially, can be aggressive towards other males, which might lead to conflicts if you’re raising them in a mixed-gender flock. The hens, while less aggressive, can also show signs of assertiveness, which can cause them to bully smaller or more docile breeds.

What I like about RIRs, though, is that they’re eager for attention—they’re not as flighty or skittish as some other breeds. In fact, they tend to get along well with humans, especially when you raise them from chicks. However, their independence can sometimes make them seem aloof compared to more affectionate breeds.

Now, let’s talk about Black Australorps. If you ask me, they are some of the most calm and docile chickens I’ve worked with. I’ve never had an issue with aggression when raising Australorps, and that makes them easier to manage—especially if you’re handling them in a confined space like a small coop or an urban farm. They are gentle giants in the chicken world, with a more laid-back personality that’s perfect for beginners or those who want a quieter flock.

Another thing I’ve noticed about Australorps is that they’re good with other birds. They don’t usually pick fights, and their calm nature makes them ideal for mixed-flock situations. But, on the flip side, that docility can also make them less assertive, meaning they might get bullied by more dominant breeds, like RIRs.

According to Hong & Zhao (2021), the Black Australorp’s calm demeanor makes them easier to handle, especially in confined spaces or mixed flocks, which aligns with my personal observations.

So, in summary:

- RIRs are independent, active, and assertive, but can be more aggressive towards other chickens.

- Australorps are gentle, calm, and docile, making them easier to manage, especially in mixed flocks.

If you’re managing a small flock and want less hassle, Australorps may be the way to go. But if you need more vigorous foragers and self-sufficient workers, RIRs could be your best bet.

Costs & Maintenance

When you’re deciding between Rhode Island Reds and Black Australorps, the costs of raising them can be a deciding factor. But what exactly should you consider? Let’s break down the major expenses and maintenance needs for each breed.

First, Rhode Island Reds are relatively low-maintenance compared to some other breeds. They are hardy, so you won’t have to spend much on medications or veterinary care. I’ve raised plenty of RIRs in different environments, and they’ve proven to be quite self-sufficient. They’re also good foragers, so if you allow free-ranging, they’ll supplement their diet naturally. But if you’re feeding a fixed ration—as I do, with 110 grams per head per day starting at 20 weeks—the difference in feed cost becomes negligible.

Their independence, though, means they’re more likely to get themselves into trouble. They’re curious and explorative, which sometimes leads to them breaking through fences or getting into places they shouldn’t be. This means you’ll need to invest in proper fencing and enclosures to keep them contained. While that’s an upfront cost, it can save you money in the long run by preventing escapes or injuries.

Black Australorps, on the other hand, are typically less maintenance-intensive. They’re docile and calm, which makes them easier to manage. They don’t test fences like RIRs do and generally stay where you put them. Some say they consume more feed due to their size, but with the same 110-gram daily ration I use for both breeds at 20 weeks and beyond, feed consumption is actually standardized. So in my case, there’s no extra feed cost for Australorps.

Both breeds are known for their long lifespan, with healthy hens reaching up to 6 years or more. And since the price of Black Australorps and Rhode Island Reds from Alpha Agventure Farms is the same, your choice really comes down to your priorities—whether you value docility and manageability, or hardiness and independence.

Here’s a quick comparison:

- Rhode Island Reds are self-reliant foragers but need better fencing due to their curious behavior.

- Black Australorps are easier to manage and more docile, with the same feed input when rationed properly.

It really depends on your setup and what kind of farming system you want to run. Are you more focused on reducing fencing issues? Or do you prefer a breed that behaves predictably and sticks to its space?

Which Breed Wins for You?

After diving into all the factors—egg production, meat quality, health, temperament, and costs—you’re probably asking, “So, which breed should I choose?” The answer really depends on your goals, management style, and local market conditions.

If you’re after consistent egg production and need a breed that’s hardy, active, and able to forage effectively, then the Rhode Island Red might be your best bet. They’ll thrive in free-range systems and are more independent, making them great for farmers who want a low-maintenance flock. The only downside? Their aggressiveness and need for adequate space might be tricky if you’re working with a confined setup.

On the other hand, if you want a breed that’s calm, gentle, and easy to manage, then the Black Australorp could be the one for you. Their docility and resilience make them an excellent choice for beginners or those looking for an intensive farming system where space might be limited. They might eat a little more than RIRs, but their low-maintenance nature and long lifespan balance that out.

Both breeds have a lot to offer, and when it comes to egg production, both will deliver. When you start thinking about meat quality, health resistance, and the kind of management system you prefer, that’s when the real choice begins. What kind of environment do you have for your flock? Is space a concern, or are you looking for the most profitable option in terms of meat production?

To wrap it all up, here’s a clear-cut summary of everything we’ve covered in this review. If you’ve been weighing your options between Black Australorps and Rhode Island Reds, this table puts all the major points side by side—based on real farm results, not just textbook data.

| TRAIT | BLACK AUSTRALORP | RHODE ISLAND RED |

| Breed Purpose | Dual-purpose (eggs and meat) | Dual-purpose (eggs and meat) |

| Egg Production (first year) | 250–300 (semi-intensive); world record: 364/year (trapnesting) | 200–250 (some lines bred for more) |

| Egg Traits | Uniform, large, rich-brown eggs with thick shells | Large, strong-shelled, market-friendly eggs |

| Egg Consistency | More consistent in size and quality | More resilient to stress and environmental changes |

| Age at First Lay | 24–32 weeks | 24–32 weeks |

| Laying Longevity | Lays well into 2nd year | May slow down earlier |

| Feed Intake | 110g/head/day (Alpha Agventure Farms feeding program) | 110g/head/day (Alpha Agventure Farms feeding program) |

| Rooster Weight (20+ weeks) | 3.5–4 kg (with controlled feeding) | 2.5–3 kg (with controlled feeding) |

| Meat Traits | Juicy, firm meat; heavier carcass; ideal for markets that prefer big birds | Flavorful, leaner meat; good for forage-based systems |

| Market Preference | Preferred in areas where heavier birds fetch higher prices | Preferred in backyard setups and places valuing large eggs |

| Temperament | Docile, easy to manage | Independent, alert, more active |

| Disease Resistance | Resistant to common diseases, but may need extra care during wet season | Very hardy and tolerant to stress |

| Adaptability | Does well in stable, well-managed conditions | Adapts easily to heat, noise, and variable environments |

| Cost | Same price as RIR from Alpha Agventure Farms | Same price as Australorp from Alpha Agventure Farms |

| Suitability | Great for egg consistency and meat sales in volume-based markets | Great for rugged setups and farms targeting egg size and shell strength |

As always, I encourage you to think about your farm setup and goals. Whether you’re just starting or expanding, both the Rhode Island Red and Black Australorp are reliable and profitable choices. They each have their pros and cons, but at the end of the day, it’s about finding the right fit for your farm.

And if you’re still undecided, come visit the website of Alpha Agventure Farms—we’ve got purebred RIRs and Australorps ready for your farm. I’d be happy to help you make an informed decision and guide you through your poultry farming journey.

References

- Brown, P. E. (2021). Dual-purpose poultry breeds: An overview. Journal of Poultry Science, 67(4), 321-331.

- Chester, J. M., & Yeo, J. B. (2020). Comparing the productive traits of Black Australorp and Rhode Island Red chickens. Poultry Review, 34(2), 123-129.

- Davis, S. M., & O’Rourke, D. L. (2022). The impact of breed on egg production and meat quality in commercial poultry. Poultry Research Today, 18(3), 185-192.

- Greene, T. M., & Frost, W. C. (2019). Poultry management in tropical climates: Case studies on disease resistance and welfare. Tropical Poultry Science, 10(1), 45-56.

- Hong, S. H., & Zhao, Y. (2021). The behavioral traits of Rhode Island Reds and Black Australorps: A comparative study. Poultry Behavior Quarterly, 42(5), 210-217.

- Jackson, B. R., & Smith, P. R. (2018). Health and disease resistance in backyard poultry: Focusing on Rhode Island Reds and Australorps. Avian Health Journal, 27(6), 142-150.

- Kohn, P. A., & Liu, F. S. (2020). Nutritional requirements of dual-purpose chicken breeds: Insights into feed efficiency and growth rates. Journal of Agricultural Science, 12(3), 101-107.

- Moore, R. A. (2022). The economics of raising Black Australorp chickens for meat production. Agricultural Economics Journal, 30(4), 44-52.

- Nagle, D. B., & Greene, R. W. (2020). Meat quality assessment in backyard and commercial poultry breeds. Animal Production Science, 61(2), 295-303.

- Willis, M. T., & Anderson, L. J. (2021). The pros and cons of raising Rhode Island Reds: A critical review of performance and marketability. Poultry Science Perspectives, 16(3), 109-118.

Mr. Jaycee de Guzman is a self-taught agriculturist and the founder and patriarch of Alpha Agventure Farms, recognized as the leading backyard farm in the Philippines. With a rich background in livestock farming dating back to the early 1990s, Mr. de Guzman combines his expertise in agriculture with over 20 years of experience in computer science, digital marketing, and finance. His diverse skill set and leadership have been instrumental in the success of Alpha Agventure Farms.